While I read a compiler book, I have struggled to understand the reason why the arithmetic operations are expressed as follows.

add = mul add'

add' = ε

add' = "+" mul add'

add' = "-" mul add'

mul = term mul'

mul = ε

mul' = "*" term mul'

mul' = "/" term mul'

term = <num>

term = "(" add ")"

That must be easy to understand those who are familiar with BNF. The calculus expression can be reduced from non-terminal, add. You can construct the LL(1) parser based on the grammar systematically as demonstrated in the book.

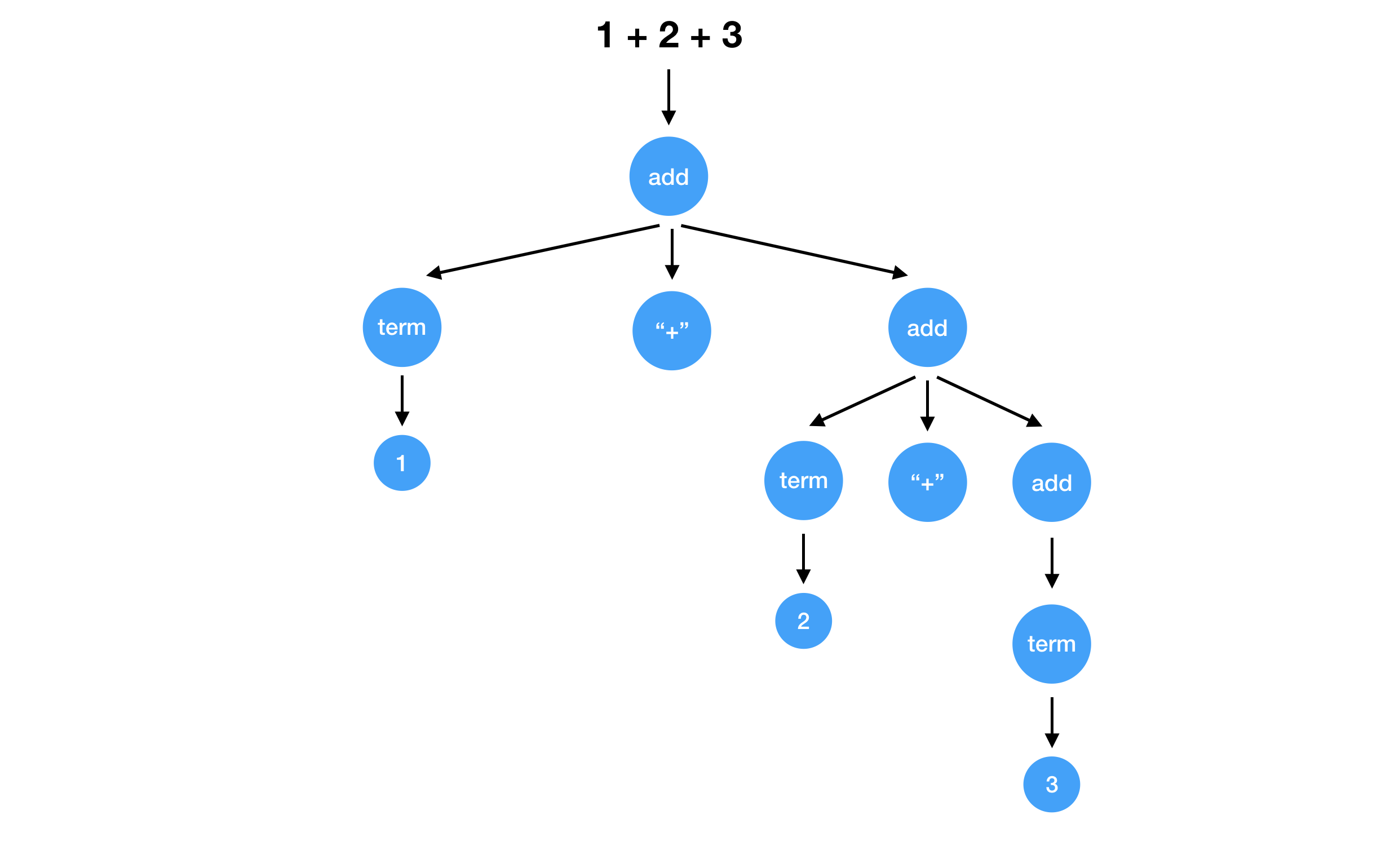

But in the beginning, it looks very redundant to me. For example, an expression 1 + (2 + 3) is interpreted as shown in the first illustration. In spite of the simplicity of the expression itself, why can the syntax tree be such complicated? There must be a good reason because the theory of compiler and context-free grammar is one of the most researched fields in computer science. In this post, I’m going to try to clarify the reason why the definition of the grammar of arithmetic operations looks redundant and complicated than I expected.

Table Of Contents

- The Simplest Definition I Could Imagine

- Another Definition Supporting Consecutive Binary Operation

- Eliminate Direct Left Recursion

The Simplest Definition I Could Imagine

First, I tried to come up with the simplest grammar definition for arithmetic operations. It has only 8 lines of the definitions.

add = mul

add = mul "+" mul

add = mul "-" mul

mul = term

mul = term "*" term

mul = term "/" term

term = <num>

term = "(" add ")"

But I found it did not work as expected immediately. It could not parse the following like 1 + 2 + 3 because add is not reduced add itself. We could not put consecutive “+” operations in the expression. In order to achieve arbitrary consecutive binary operations, we should have add itself in either left or right of the binary operation.

Another Definition Supporting Consecutive Binary Operation

add = mul

add = add "+" mul

add = add "-" mul

mul = term

mul = mul "*" term

mul = mul "/" term

term = <num>

term = "(" add ")"

It looks good but I wondered whether it is possible to mul before add in the second line.

add = mul "+" add

Actually, it’s possible. The order of these non-terminator decides the priority of how each operator is applied. Let’s say we have a grammar defined like this. You can see the right operand of “+” is evaluated first.

add = term

add = term "+" add

On the other hand, this grammar leads the left operand is evaluated first.

add = term

add = add "+" term

So overall, the difference between add "+" mul and mul "+" add will lead the difference of the associativity of the same operators. Associativity of the most arithmetic operators is left to right. It’s natural to use add "+" mul so that we can get the syntax tree with the deep left child.

But there is one problem called Left Recursion. When you try to implement a parser of this grammar, the function to parse the node add will look like this.

add()

{

add(); // Cause infinite recursion

readPlusToken();

mul();

}

As function add calls add at the beginning, it causes an infinite loop so that we are not able to make progress at all. In order to avoid this type of problem, it’s necessary to rewrite the grammar a little bit.

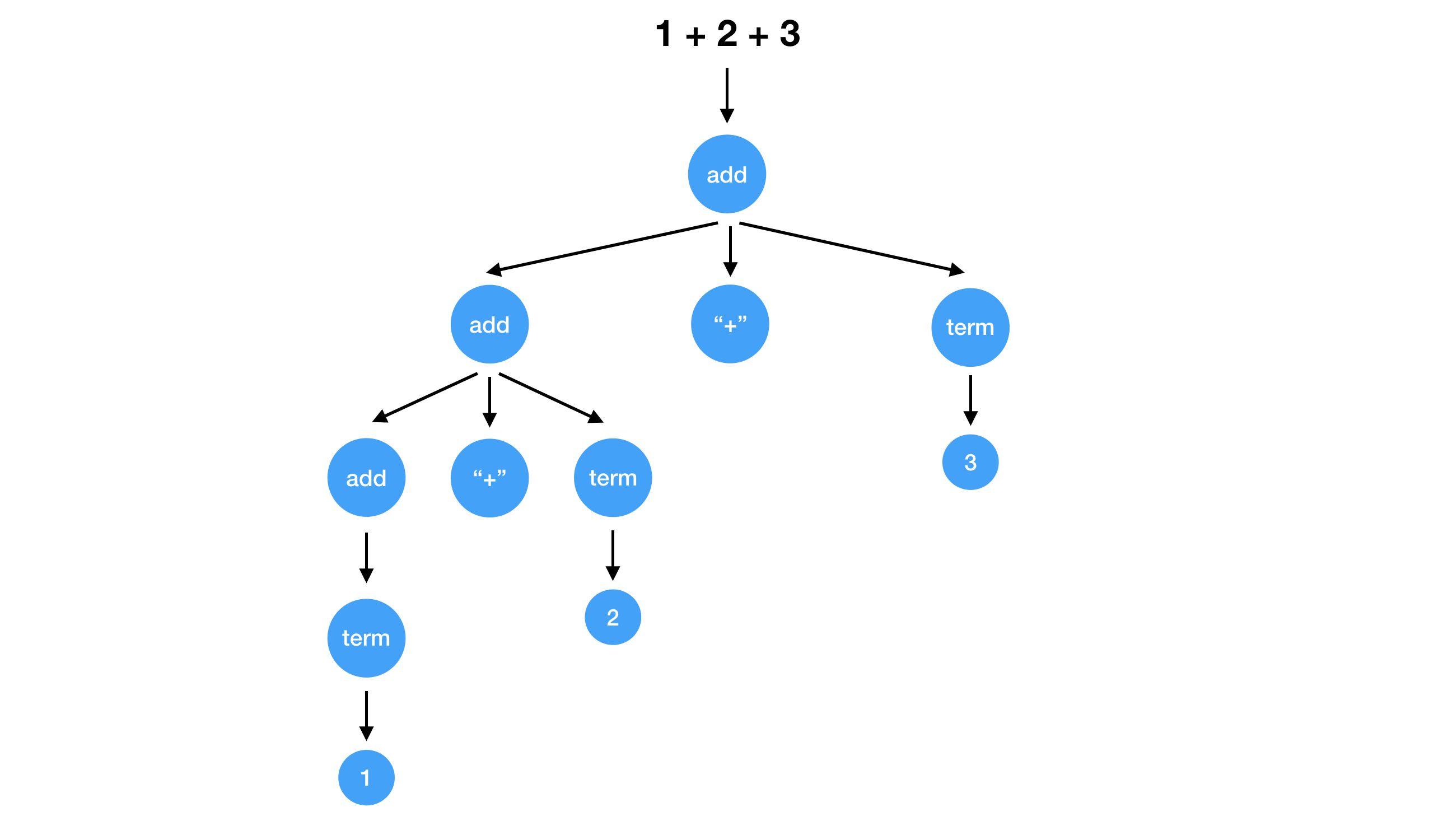

Eliminate Direct Left Recursion

Generally, a grammar is called left recursive if and only if there is a non-terminal symbol which can be derived with itself as the leftmost symbol. The left recursion which can be written as follows is called direct left recursion especially.

\begin{equation} A \Rightarrow A\alpha | \beta \end{equation}

\(\alpha\) and \(\beta\) are the terminal symbols. Simply writing a parser with this grammar cause the infinite loop. How can we remove the direct left recursion?

Let’s assume that \(\beta\) is a terminal or non-terminal symbol which does not start with A. Then we can rewrite the rule like this.

\begin{equation} A \Rightarrow \beta A’ \end{equation}

\begin{equation} A’ \Rightarrow \alpha A’ | \epsilon \end{equation}

The rewritten rule enables us to implement a parser free from infinite recursion. Let’s try to rewrite the rule I introduced at the beginning to eliminate left recursion. This rule causes the left recursion as aforementioned.

add = mul

add = add "+" mul

add = add "-" mul

Let’s introduce new symbol add'. Assuming mul corresponds to \(\beta\) and “+” or “-“ does to \(\alpha\).

add = mul add'

add' = ε

add' = "+" mul add'

add' = "-" mul add'

This rule can be written as follows.

add()

{

mul();

add_p();

}

add_p()

{

if (isPlusToken()) {

readPlusToken();

mul();

add_p();

}

else if(isMinusToken()) {

readMinusToken();

mul();

add_p();

}

}

But in practice, it seems to be common to write like this. That’s short, simple and efficient than the previous one.

add()

{

mul();

for (;;) {

if (isPlusToken()) {

readPlusToken();

mul();

}

else if (isMinusToken()) {

readMinusToken();

mul();

}

}

}

Finally, we can get the grammar definition illustrated at the beginning of the article. The grammar is created by considering the associativity of binary operators and the effort to eliminate the problem of direct left recursion.

There are many books to learn the theory of compiler but here is the long living bible in the compiler field. “Compilers: Principles, Techniques, and Tools (2nd Edition)”.

It may be overkill for the people who just try to create a compiler as their hobby and hard to complete the entire contents. But it will provide meaningful experience as a whole for sure.

Thanks!